find your perfect postgrad program

Search our Database of 30,000 Courses

Humanities Research: Crime and punishment

Famous and infamous characters from Britain’s past, and nearly 200,000 other defendants – the hard work of three British historians has brought the bloodstained past of London’s Old Bailey courthouse to life in a fascinating online archive. Chris Leadbeater explains

|

The Proceedings archive Old Bailey Online |

At 12 feet high, she is one of the tallest women in London. She stands, arms stretched out, a raised sword in her right hand, a set of scales hanging from her left. She is Lady Justice, and she is a celebrity – the gold-leaf statue that adorns the dome of the Central Criminal Court for England and Wales, a court more widely known as the Old Bailey.

The Old Bailey, in its ‘modern’ form, appeared on the map of London in 1673 and, although it has been expanded several times in the interim, it has performed the same role in the same place ever since – it is the main criminal court for London.

A place of despair?

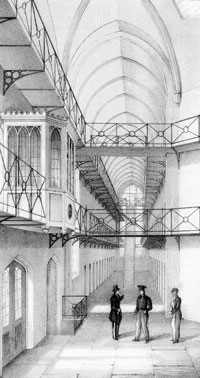

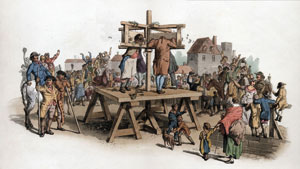

Three centuries ago, the Old Bailey was a place of horror and death, the last stop-off point for accused men and women who, before their trial, festered in the notorious Newgate Gaol next door – then met their end (from 1783, at least) on the gallows that stood outside the prison. And yet, incredibly, in the 17th and 18th centuries, the Old Bailey was a popular place, a location where crowds gathered to see alleged killers interrogated – or hung from a rope. Crime was a hot topic in the England of the late 17th century – highwaymen were celebrities and criminal biographies were bestsellers. So much so, that, in 1674, London’s new court spawned a publishing phenomenon that was to last for over two centuries.

The Proceedings

April 1674 saw the first printing of The Proceedings of the Old Bailey , a summary of the latest trials. Unofficial, sensational and short on hard information, the document was nevertheless devoured by the crime-obsessed public. Quickly, the Proceedings grew into a regular periodical packed with dirty deeds. Over time, the Proceedings became more detailed, providing coverage of key evidence and verbatim testimony from the big cases. In 1778, the City of London demanded that they be a ‘true, fair, and perfect narrative’ of all trials held at the Old Bailey, effectively turning what had been a gossip sheet into an official legal publication. By the time the Old Bailey was formally rechristened the Central Criminal Court in 1834, these once bloody tales were a far more sober record, targeted squarely at the legal community.

The Proceedings were scrapped in 1913, six years after the Criminal Appeal Act (which required the taking of full shorthand notes at every trial) had made them obsolete. But they had become in 239 years a considerable archive not only of matters at the Old Bailey, but also of the lives of everyday Londoners, of the dirt under a city’s fingernails; an archive that has now been brought into the 21st century by a team of British historians.

Opening it up

Until 1999, the Proceedings were only really known to academic figures – including two experts on London in the 18th century, Professor Tim Hitchcock of the University of Hertfordshire and Professor Robert Shoemaker of the University of Sheffield. Each had worked with the Proceedings , using the source in its most modern format, a set of microfilm reels, which, though made in the 1980s, was hard to search for information. Frustrated by this, they formed a plan to make the Proceedings more widely available.

Until 1999, the Proceedings were only really known to academic figures – including two experts on London in the 18th century, Professor Tim Hitchcock of the University of Hertfordshire and Professor Robert Shoemaker of the University of Sheffield. Each had worked with the Proceedings , using the source in its most modern format, a set of microfilm reels, which, though made in the 1980s, was hard to search for information. Frustrated by this, they formed a plan to make the Proceedings more widely available.

‘We knew the printed trial accounts existed and that they were a valuable source of material on daily life in 18th-century London,’ Professor Shoemaker explains. ‘But it was impossible to make the most of them. In order to find what you wanted, you had to sift through this enormous haystack of microfilm. We realised the source would benefit from being electronically searchable, so we applied for grants to put it online.’

So began a Herculean task that would take almost a decade. The first job was to tackle the era covered by the microfilm – which in itself presented problems. The makers of the microfilm had only reproduced the Proceedings from 1714 to 1834, meaning that the first 40 years had to be unearthed and included. It would not be a simple process. ‘The quality of the microfilm, and of the original print, was quite poor,’ Shoemaker continues. ‘So the text had to be typed by hand twice. That way, a computer could compare the two versions for errors.’ This part of the procedure was performed by the specialist Higher Education Digitisation Service at the University of Hertfordshire before work moved to the University of Sheffield’s Humanities Research Institute, where the tiring business of making the raw record electronically searchable began.

‘Once the text came to us, we had to give it structure by inserting electronic tags that would indicate the beginning and end of each trial, the names of the defendants, the type of crime, the type of punishment – all those pieces of information,’ Professor Shoemaker adds. ‘Five people worked for two years as data developers, giving the text that crucial framework. There were a lot of person years involved in this project.’

The next stage

This first batch of the Proceedings went online in 2003. But the job was still only half done. The 1980s microfilm ended at 1834, when the Old Bailey had been renamed and the title of the Proceedings changed to The Whole Proceedings of the Central Criminal Court .

‘The later accounts weren’t known to us at first, partly because we’re 18th-century historians,’ Shoemaker explains. ‘We weren’t aware that the publication continued until we were well involved with the first phase of the project. But when we realised that the later material was available, we chose to seek additional funding.’

The second phase was simpler, especially once Professor Clive Emsley, a historian of the 19th century at the Open University, joined the team. An American microfilm collection covering the period to 1913 – in better condition than the first-phase film – had been found, a development that meant the accounts only had to be typed once. Optical character-recognition technology – an advanced form of scanning – was used to check for errors and, by April this year, the results were online. The archive, dating back to 1674, now consists of 197,745 trials, 110,000 pages of text and 120

million words.

Intriguing cases

This archive ( www.oldbaileyonline.org ) is a treasure trove that lets you dive into the Old Bailey’s past, and resurface with fascinating nuggets of information on major crimes and cases. Dip into 1910, for example, and you find the trial of the notorious Dr Hawley Crippen, who was convicted of murdering his wife Cora, apparently using poison – shortly before he dismembered her body and dissolved her organs in acid.

This archive ( www.oldbaileyonline.org ) is a treasure trove that lets you dive into the Old Bailey’s past, and resurface with fascinating nuggets of information on major crimes and cases. Dip into 1910, for example, and you find the trial of the notorious Dr Hawley Crippen, who was convicted of murdering his wife Cora, apparently using poison – shortly before he dismembered her body and dissolved her organs in acid.

The account includes the damning evidence of Augustus Pepper, a surgeon at London University, who identified a mark on the headless, limbless torso found underneath Crippen’s basement floor as a scar consistent with Cora’s medical history. ‘I came to the conclusion that this was a scar,’ he reveals, ‘at my first examination... I had heard that Mrs Crippen had had an operation there... I do not agree that the condition of that piece of skin made it difficult to say whether that mark was a scar.’ Crippen was hanged.

Another intriguing case is the 1850 attack on Queen Victoria in London that left her bruised and shaken. A witness, Samuel Cowling, described how he saw the defendant, Robert Pate, hit the Queen with a cane as her open carriage passed through a crowd: ‘At that moment [the carriage] was in front of us... the prisoner made one step... and struck Her Majesty... it was a hard blow. I should not like it to have come upon my own forehead.’ Pate pleaded insanity, but was convicted and transported to Tasmania.

Visit the 18th century, when the Proceedings were at their most populist, and you find lurid details galore – such as the trial of Jonathan Wilde, a ‘thief-taker’ who thrived in London between 1710 and 1725. ‘Thief-takers operated on the fringes of legality,’ Shoemaker explains. ‘They made a profit by getting government rewards for informing on and turning in criminals – but also returned stolen goods to victims for a price.’ Wilde was an expert exponent of the art, running his own band of thieves. He sold the gang’s ill-gotten gains back to their rightful owners – or blackmailed them if the items were of a sensitive nature – while ‘identifying’ thieves in rival thief-taking outfits as the perpetrators of the thefts (or even his own men if they crossed him) – all while marketing himself as a semi-official policeman providing a legitimate service.

His villainy was finally exposed in 1725, and he was tried for crimes including theft and perverting justice. But even here, he was up to his tricks. His slippery character is clear in the Proceedings , which record that he distributed about the court a list of the many thieves he had ‘apprehended’, claiming that his enemies wanted to destroy him. Sadly for Wilde, his actions merely caused ‘the King’s Counsel to observe, That such Practices were unwarrantable, and not to be suffer’d in any Court of Justice. That this was apparently intended to... influence the Jury’. His execution was a widely attended event. ‘Wilde antagonised a lot of people,’ Shoemaker adds. ‘When he was hanged, the crowd even got angry with the executioner because it took so long to dispatch him.’

Fascinating insights

There are numerous lessons to be gleaned from a study of the Proceedings – one being the way punishments became more humane and less physical as the decades passed.

There are numerous lessons to be gleaned from a study of the Proceedings – one being the way punishments became more humane and less physical as the decades passed.

‘If you study the 18th-century trials, you get a sense of the range of punishments,’ Shoemaker adds. ‘These included burning women at the stake, hanging, whipping, branding. But you can tell another story, one of progress. Clearly, from the early 19th century, there is a decline in the number of people sentenced to hang. And, in the 18th century, a decline in the number of people branded or whipped. You see a move from punishing the body to punishing via imprisonment and trying to reform the mind.’

The Proceedings also offer a reminder that terrorism – such an area of worry in the 21st century – is nothing new. It was alive in the late 19th century, when anarchism – an opposition to all forms of government and authority – was a threat. The Proceedings for April 1894 carry the trial of Giuseppe Farnara and Francis Polti, Italians charged with possession of explosive substances ‘with intent to endanger life and property’. The account shows Farnara, full of the righteous indignation of a man convinced he is fighting a just cause, exclaiming: ‘Yes; I plead guilty; I had the intention to blow up the capitalists, and all the middle classes.’ Both men were convicted and imprisoned.

Other discernible trends included the development of police powers and techniques. Where Jonathan Wilde was able to act with virtual impunity in the face of very limited policing in the 1720s, the account of the Farnara–Polti case shows that Scotland Yard had the pair under close surveillance long before they were able to cause any damage.

Likewise, you can watch the evolution of the English language over nearly 250 years, from the archaic ‘he threw down the Glass, and in making hast away dropt of his Hat’, in the case of a man accused of stealing a mirror in 1674, through to the recognisably modern wording of the final Proceedings in 1913. ‘Clearly, this is a written archive,’ Robert Shoemaker continues. ‘But these are frequently accounts of oral testimonies and so you can trace how the language has been spoken over time.’

A note of caution

Of course, this is not a perfect resource. Even in 1913, the Proceedings offered only highlights of any trial, and the 17th- and 18th-century accounts were often wilfully dramatic – though not necessarily unreliable. ‘These accounts are not misleading,’ says Professor Shoemaker. ‘They don’t tell lies. But they don’t report everything. People should treat the Proceedings like any historical source. With caution.’

A great asset

Nevertheless, the Old Bailey Proceedings Online will be – and has already been – of huge assistance to all manner of people – from school students and undergraduates to those completing postgraduate degrees and PhD research projects, and on to full-time historians. Then there are those who visit the archive as they trace their family tree.

‘We’re aware, from where the site crops up as a footnote in publications, that it has been used by a wide range of people in academia,’ Shoemaker reveals. ‘But we have visitors from outside academia. There is a global spread – everywhere from America, Canada and Australia to Brazil, Japan and Norway.’ The site has had over ten million visits since its launch in 2003. ‘We always knew that the project would be of interest to a wide audience,’ he smiles. ‘But the scale of the interest has surprised even us.’

Chris Leadbeater is a freelance writer who specialises in education, arts and music.

Read other Humanities research papers, including research from 2006 about the Popularity of the Novel and 2007 research on Breaking Down The Barriers.